Chapter 9: THE GREAT DIVIDE: THE BREAK BETWEEN THE AFRO-AMERICAN SOCIALISTS AND NATIONALISTS

In the tumultuous years 1919-1920, as the SP and the IWW suffered demoralization and defeat at the hands of an increasingly ferocious and effective repression, Garvey distanced himself from the Afro-American supporters of these outcast groups. Increasingly emphasizing race over class, Garvey enlisted ex-Socialist Harrison as a key ally. In response, Afro-American radicals launched the Emancipator, a weekly newspaper propounding a positive vision of social change greatly resembling that advocated by the Messenger. Unlike Randolph's magazine, however, the Emancipator explicitly attacked Garvey. The Socialists were at loggerheads with the UNIA, therefore, long before Garvey's sharp rightward lurch of 1921. Indeed, government repression of the Left, combined with the very real chasm between the Socialists and Nationalists, ensured an eventual break between the supporters of rival philosophies, organizations, and publications.

Harrison, who had retained key aspects of Socialist class-based ideology even while embracing black nationalism, briefly bridged the widening chasm before joining forces with Garvey. While Randolph's Messenger advocated a socialism concerned with racial injustice, and Garvey's Negro World propounded its "race first" philosophy, Harrison briefly revived his Voice, succeeded by a brief-lived New Negro. (Harrison wrote copiously for the latter publication, but was not listed on the masthead as an editor.) In the two years (1918-1919) after the demise of the first Voice, Harrison continued his advocacy of black self-help and internationalism. These themes, and a new hostility towards the Socialist party and its black adherents, won Harrison appointment as an associate editor of the Negro World in January 1920.

Unlike Du Bois, Harrison remained militant after America's entry into the war. He was a co-chair of Monroe Trotter's National Colored Liberty Congress, which met in Washington, D.C., in early July 1918 (only days after the government-convened meeting of Negro editors, which had directly professed its loyalty). This Congress used Wilsonian language in demanding the end of segregation and discrimination in all federal offices, buildings, and enterprises (including the government-run railroads), the abolition of lynching, the enforcement of the Reconstruction amendments, and "that the words of the President of the United States of America [on liberty and democracy] be applied to all at home."[1]

At the same time Harrison announced that the Voice's "thousands of friends among the common people" had besieged newsdealers and asked for their favorite paper; this caused its "resurrection." When a white man offered Harrison $10,000 for half-ownership of the revived Voice, Harrison had refused him because had he accepted "it would not have been your paper. We want to see at least one Negro paper buttressed on the love and devotion of the masses of our own race." The Voice's policy would be "shaped by ourselves alone." Harrison denounced disloyal race leaders in the pay of their enemies and exclaimed that the Negro press, by acquiescing in the execution of thirteen of the Houston rebels (black soldiers who had retaliated against racist abuse), had "licked the boot that kicked them." He sold shares in the new Voice for $10 each and, like Garvey, told his supporters that "if you buy as you should your money will be paying you dividends in the years to come."[2]

Harrison supported himself during these years by speaking on the streets and selling copies of his works; he also spoke in front of organized meetings. Two secret police agents described his powerful impact upon his audiences. One, a white, described the explosive impact of Harrison's District of Columbia tour, saying that "the conservative colored population of Washington... listened to him in awed silence.... During this brief period of six weeks Mr. Harrison has developed a very large following in the city of Washington, just as he did in New York."[3]

Major W.H. Loving, an important black agent in charge of monitoring black radicals, had an equally high opinion of Harrison's abilities. Harrison

is a scholar of broad learning and a radical propagandist. Most of his time is spent in lecture tours in cities having large Negro populations. He is not affiliated with any political party and freely criticizes all of them. He differs from other Negro radicals, in that his methods are purely scholastic. He typifies the professor lecturing to his classes rather than a soap box orator appealing to popular clamor.... Thoroughly versed in history and sociology, Mr. Harrison is a very convincing speaker. I consider his influence to be more far reaching than that of any other individual radical because his subtle propaganda, delivered in such scholastic language and backed by the facts of history, carries an appeal to reason that reaches the more thoughtful and conservative class of Negroes who could not be reached by the "cyclone" methods of the more extreme radicals.

Loving considered Harrison's lectures "a preparatory school for radical thought" that "prepare[d] the minds of conservative Negroes for the more extreme doctrines of Socialism. Without any deliberate intent to serve in such a capacity, he is the drill master training recruits for the Socialist army led by the extreme radicals, Messrs. Owen and Randolph."[4] Harrison also addressed mixed audiences, urging that black and white workers unite for their own betterment during the war crisis.

In tones that must have pleased Garvey, Harrison insisted that "the Negroes of America must cease whining and complaining.... [and] must cease looking up to others for help which is within their own grasp. They should learn the history of their own race and the contributions it has made to civilization. On this rock of self-knowledge they must build their house of racial self-respect before they can gain the respect and friendship of the white race."[5] He denounced the (white) "professional friends" of the Negro who diverted, betrayed, and dominated the blacks they purported to help. "We are not children" and "need no benevolent dictators," he said. Blacks, not whites, must shape Afro-American policy. Foreshadowing radical blacks of the 1960s, Harrison exclaimed that "Now, that we are demanding the whole loaf, they are begging for half, and are angry at us for going further than they think 'nice.'.... If friendship is to mean compulsory compromise foisted on us by kindly white people, or by cultured Negroes whose ideal is the imitation of the urbane acquiescence of these white friends, then we had better learn to look a gift horse in the mouth."[6]

African-Americans could learn from others, however--from white radicals and from anti-imperialists of color. Harrison urged that African Americans study "that larger world where millions are in motion," and "keep well informed of the trend of that motion and of its range and possibilities. If our problem here is really a part of a great world-wide problem, we must... link up with the attempts being made elsewhere to solve other parts."[7]

Du Bois and the NAACP found themselves sharply assailed (in terms reminiscent of Du Bois's critique of Washington and those of Randolph for Du Bois) for their accommodationist philosophy and outmoded educational ideals. Du Bois, worried by governmental repression and angling for a wartime captaincy in the Military Intelligence Division of the secret police, undermined Harrison's militant Liberty Congress of June 1918. He also pledged fealty to Woodrow Wilson's terrorist and white supremacist state in his infamous "Close Ranks" editorial in the July 1918 Crisis. Although Du Bois and others lied about the circumstances surrounding these events, Harrison recognized that "the racial resolution of the [black] leaders had been tampered with" and that Du Bois, for his own personal gain, was complicit.[8]

Harrison also attacked Du Bois's beau ideals, classically educated gentlemen, as "quaint fossils" who stuffed themselves with old, dead knowledge and remained ignorant of "the modern world, its power of change and travel and the mighty range of its ideas." Rather than learn dead languages and theologies, blacks must "study engineering and physics, chemistry and commerce, agriculture and industry; let us learn more of nitrates, of copper, rubber and electricity; so we will know why Belgium, France, England and Germany want to be in Africa."[9] For Harrison, Du Bois's remedy for lynching and other forms of racial oppression was just as ineffectual as his effete gentleman's education. Piteous appeals and "frantic letters" would not stop lynching.

But suppose the common Negro.... lets it be known that for the life of every Negro soldier or civilian, two "crackers" will die? Suppose he lets them know that it will be as costly to kill Negroes as it would be to kill real people? Then indeed the Ku Klux would be met upon its own ground.... Lead and steel, fire and poison are just as potent against "crackers" as they were against Germans, and democracy is as well worth fighting for in Tennessee as ever it was on the plains of France. Not until the Negroes of the south recognize this will anybody else recognize it for them.[10]

The "father of Harlem radicalism" also decisively broke with the Socialist party. Harrison's first major attack on black Socialists, "Two Negro Radicalisms," appeared in the short-lived New Negro in October 1919, shortly after Garvey had cashiered W. A. Domingo, editor of the Negro World, for his advocacy of Socialist doctrines. Harrison, whose own Liberty League and publications had faltered, probably saw Garvey's UNIA as a fertile field for his own literary and "race first" efforts. Harrison began by remarking that, in contrast to the situation of only a few years ago, "Negroes differ on all those great questions on which white thinkers differ, and there are Negroes of every imaginable stripe." But Harrison castigated those Socialists (especially black Socialists) who took credit for this radical upsurge. Rather, the Great War, with its "great advertising campaign for democracy and the promises which were held out to all subject peoples, fertilized the Race Consciousness of the Negro people." Black concentration in Northern cities, which offered greater freedom and the opportunities for the creation of authentic Afro-American culture and institutions, further radicalized and energized blacks. SP emphasis on class above race was misguided because "the cause of 'radicalism' among American Negroes is international." Blacks resented "not the exploitation of laborers by capitalists; but the social, political and economic subjection of colored peoples by white."[11]

That the "Color Line" trumped the "Class Line" was "a fact of Negro consciousness as well as a fact of externals," Harrison continued. "On the part of the whites, the motive [for racism and the racial caste system] was originally economic; but it is no longer purely so.... Similarity of suffering has produced in all lands where whites rule colored races a certain similarity of sentiment, viz.: a racial revulsion of racial feeling.... The fact presented to their minds is one of race, and in terms of race do they react to it."[12] Some blacks, therefore, embraced Socialism and Bolshevism for their own racial reasons:

Undoubtedly some of these newly-awakened Negroes will take to Socialism and Bolshevism. But here again the reason is racial. Since they suffer racially from the world as at present organized by the white race, some of their ablest hold that it is "good play" to encourage and give aid to every subversive movement within that white world which makes for its destruction "as it is." For by its subversion they have much to gain and nothing to lose. Yet they build upon their own foundations.[13]

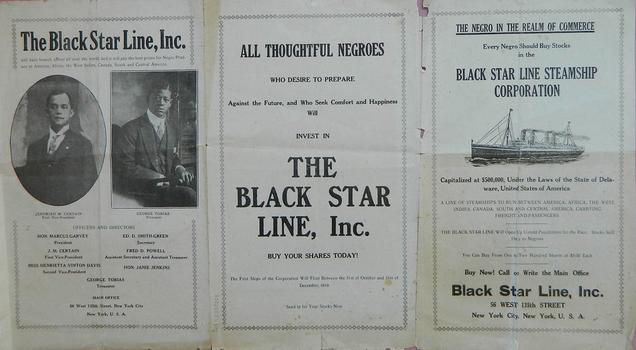

Afro-American race consciousness, therefore, took the form of resisting white oppression as well as the more positive tactics of "seeking racial independence in business and reaching out into new fields of endeavor. One of the most taking enterprises at the present is The Black Star Line, "a steamship enterprise being floated by Marcus Garvey of New York. Garvey's project (whatever may be its ultimate fate) has attracted tens of thousands of Negroes." White-oriented black radicals such as Randolph and Owen addressed tiny audiences while Marcus Garvey "fills the largest halls and the Negro people rain money upon him" because he emphasized "racialism, race consciousness, racial solidarity--things taught first in 1917 by The Voice and the Liberty League." However, Harrison also said (in a phrase excised from the version he reprinted in When Africa Awakes) that Garvey's "education and intelligence are markedly inferior to those" of the of black Socialists--hardly a statement designed to appeal to the UNIA leader.[14]

In 1919 Harrison also endorsed Garvey's two main enterprises, the Black Star Line and the Back to Africa movement. According to a secret police report, Harrison spoke at the Rush Memorial Church (October 19, 1919) and proclaimed "that nations and people never rose to power without ships; that by means of ships they could carry passengers and men to other countries, that they could be passed through as working men; that they could get their literature through; that the promotion of the Black Star Line was not for its present value but its future value." That same evening, speaking at the Lafayette Hotel, Harrison "said that negroes should centralize like the Irish and other nations in one place which is practically their fatherland, [and] that Africa was their fatherland. That if they kept together they could create a power in Africa...."[15]

At this time, Garvey was also breaking from the black Socialists who had been his early allies. Garvey had spoken at a Harlem rally featuring Randolph in 1916. In December 1918 he had helped Randolph, Owen, Monroe Trotter (militant editor of the Boston Guardian and founder of the National Equal Rights League), and others form the International League of Darker Races, whose goal was securing justice for Africans at the Versailles Peace Conference. The UNIA elected Randolph and Ida B. Wells as delegates to that august gathering. (Denied passports, they could not attend). When Garvey, discouraged over infighting within the UNIA, contemplated returning to Jamaica in the spring of 1917, Harrison and Domingo dissuaded him. Domingo, Harrison, Briggs, and McKay all worked with the UNIA, "educating its membership in the class-struggle nature of the Negro problem" and inculcating the tenets of Socialism. Domingo, a close friend of Randolph and Owen, greatly influenced Garvey, teaching him parliamentary procedure, showing him the writings of the Pan-Africanist Edward Blyden, and introducing him to Henry Rogowski, the publisher of the Socialist New York Call, who extended Garvey the credit with which he launched the Negro World.[16]

Domingo became editor of that UNIA organ, and Garvey gave him free reign. Simultaneously serving as a Messenger contributing editor, Domingo sprinkled the Negro World with articles from the Socialist press and with his own Socialist editorials, thus injecting a class analysis that differed substantially from Garvey's focus on race. The Negro World endorsed the entire Socialist ticket in the 1918 elections, especially plugging the Negro SP candidates, Randolph, Owen, and George Frazier Miller. Although the Socialists responded with warmth, these endorsements aroused the first secret police surveillance (by the Bureau of Investigation) of the Negro World. Garvey no doubt noted the defeat of the entire Socialist ticket. But in May and June 1919 the Negro World printed and extolled the manifesto of the Third International Congress, including its peroration: "Slaves of the colonies in Africa and Asia! The hour of proletarian dictatorship in Europe will be the hour of your release!" As the Wilson administration's reign of terror against radicals, immigrants, and blacks intensified, Garvey, who was vulnerable on all three counts, found himself under intensive surveillance and distanced himself from political radicalism. Then, on June 21, 1919, agents of the Red-baiting Lusk Committee, raiding the SP-affiliated Rand School, seized a draft copy of an important Domingo pamphlet.[17]

Domingo's "Socialism Imperilled" addressed white Socialists on the Right (those placing their hopes in electoral victory) and the Left (the revolutionaries), warning that their neglect of twelve million African Americans was "the greatest potential menace to the establishment of Socialism in America whether by means of the ballot or through a dictatorship of the proletariat." African Americans constituted a united group of twelve million proletarians "without whose help no radical movement in America can hope to succeed." Summarizing his own reasons for working within the UNIA, Domingo said that because blacks "react to prejudice and discrimination by becoming distinctly race conscious," the SP must, as a matter of self-preservation, "transmute the race consciousness of Negroes into class consciousness." [18]

Domingo assailed the "purely theoretical and dogmatic assumption" that blacks, as the most oppressed proletarians, would inevitably side with their class at the decisive moment. Afro-Americans were presently "the most benighted section of the American proletariat" and "the most pathetically 'Americans'." They had fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War, against their racial compatriot Aguinaldo during the U.S. subjugation of the Philippines, and finally for the United States during World War I. They could easily become "the black White Guards of America," enthusiastic mercenaries who would drown the social revolution in oceans of blood.[19] Domingo reminded the Socialists that blacks hated the AFL for its racist policies and identified the SP with those policies. Blacks felt gratitude towards rich white capitalists who provided jobs, endowed black schools and colleges (which trained "potential industrial scabs"), and provided black churches with stained-glass windows, organs, and cash. Furthermore, the churches, "the real source of Negro opinion," were "usually presided over by the graduates of schools endowed by Northern philanthropists, and true to their training [the preachers] praise the rich while inveighing against the laboring class." The plutocratic Republican party subvented the Negro press through advertising. "Thus every medium of Negro thought functions in the interests of capital."[20]

Black workers, Domingo continued, constituted a distinct caste of service workers who waited upon the rich, absorbed their values, and depended upon them for tips. They were isolated from the rest of the working class, especially the radicals. "Servants unconsciously imbibe their masters' psychology and so do Negroes," who were "docile and full of respect for wealth and authority." The plutocrats could reward individual loyal Negroes with prestige and advancement and placate the race with token and symbolic gestures, thus gratifying "the pathetic and morbid desire on the part of Negroes to gain [the] prominence which was denied them in almost every walk of life." Socialist attacks on religion and the U.S. Constitution, however necessary, would alienate blacks unless they were educated and recruited. Afro-Americans, however, feared humiliation and abuse if they attended radical meetings.[21]

The example of Finland, Domingo warned, demonstrated that a single armed man could subdue five hundred unarmed people, while the Czech troops fighting against the Soviet Union showed "how the just national aspirations of the oppressed people can be so successfully manipulated that they become instruments of their own ultimate enslavement." Socialists who relied upon "the purely theoretical syllogism" that proletarian blacks must support the revolution, ignored the proactive Bolshevik policy which "encouraged the nationalistic ambitions of Ireland, India, and Egypt." Lenin "uses realities, not theories," in his dealings with oppressed nationalities; similarly, the danger of black counter-revolution "must not be ignored by a gesture or met by a theory. It must be removed."[22]

In Domingo's eyes the IWW exemplified a racial realism that addressed specific appeals to distinct groups, rather than justifying neglect on the spurious grounds "that their appeals were made to all, and not to particular groups of the working class."[23] Socialists must emphatically denounce racial injustices, overturn union racism, and subsidize a special literature and expert speakers (black and white) addressing Afro-American concerns. Negroes were best approached through the mediums "used by the master class. Let Negro ministers and newspapers preach Socialism and the Negro race will be converted to it."[24] Domingo acknowledged that the black churches were presently off limits, but urged generous financial support for struggling black radical newspapers and periodicals.

Domingo reminded white radicals that Socialism could not flourish in isolation. "If America with her boundless resources remains non-Socialist, she will be a menace to world Socialism, and America can remain non-Socialist if 12,000,000 Negroes so will it." Yet most Socialists "do not comprehend their peril. Instead, they sentimentally flirt with the far distant problems of India and China in blissful disregard of the material fact that they will never be in a position to render tangible aid to these oppressed peoples until they succeed in making allies out of American Negroes. But perhaps this attitude on the part of American radicals is because of the fact that they are Americans and share the typical white American psychology towards Negroes. If this is so, then their radicalism is not genuine and is deservedly doomed to failure."[25]

The Lusk Committee's seizure of "Socialism Imperilled" created a public sensation. Domingo's pamphlet was widely discussed in the mainstream press. The police prohibited two meetings scheduled for July 13th at the Palace Casino, at which Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and Domingo were to speak, "on account of the IWW connection of these two speakers." Meanwhile, the right-wing National Security League mounted plans for counter-propaganda among four thousand black school teachers in the South. On July 28, 1919, the New York Times, breathlessly exclaiming that "Reds Try to Stir Negroes To Revolt," claimed that "the negroes of this country are the object of a vicious, and apparently well-financed propaganda, which is directed against white people." The aim of this agitation, backed by the IWW, the SP, and the anarchists, was to foment "discontent among the negroes, particularly the uneducated class in the Southern States." On August 5 the district attorney sent for Garvey and grilled him about his connections with the IWW, the SP, and the anarchists. The district attorney extorted a promise from Garvey: he would tone down his public utterances and cease selling Black Star Line stock. On August 16, 1919, Major W.H. Loving warned the United States that "several thousands of Negro laborers have joined [the IWW] in response to a vigorous campaign launched by its leaders" and that the UNIA "has aligned itself with the radical forces now active throughout the country."[26]

For some time black radicals had attempted to inject a revolutionary class analysis into the UNIA's doctrine and program. Garvey must have seen this as undermining his own race-based ideology, threatening his personal power, and risking the wrath of Red-baiting authorities. At any rate, Garvey responded by stating, in the Negro World of July 19, that the UNIA "has absolutely no association with any political party. We do not accept money from politicians, nor political parties.... Republicans, Democrats and Socialists are all the same to us--they are all white men, and to our knowledge, all of them join together and lynch and burn Negroes.... The only politics that we indulge in and are supporting is that of the New Negro Party of the world. We are four hundred million strong in such a party."[27] He also initiated disciplinary proceedings against Domingo for contradicting UNIA doctrine in the pages of the Negro World. Perhaps hoping to assuage Garvey's wrath, Domingo enthusiastically endorsed "Race First!" on July 26. Giving Harrison credit for coining the phrase, Domingo called it "a succinct paraphrase, for purposes of Negro propaganda and advancement, of the practices of all other races, particularly the white race." Blacks necessarily assumed "an essentially defensive role," while whites "aggressively misapplied" arguments of "Race First" when discriminating against Negroes. "But it is the same principle defensively and intelligently applied that makes the Chinese a self-sufficient people, although forming but a very small percent of the population of New York, the West Indies, and other territories outside of China where they reside.[28]

The same cause, Domingo continued, partly explained the success of the Jews. Although critics "argued that race first is selfishness, and as such will not remove the reasons that called it into being," fire fights fire and steel cuts steel. "Failure on the part of the oppressed to organize in terms of self as opposed to similar kinds of organizations on the part of their oppressors must naturally make their oppression more thorough." The doctrine of Negro First "finds its highest justification in the practices and methods of their oppressors." Until spears are beaten into plowshares "it devolves upon all oppressed peoples to avail themselves of every weapon that may be effective in defeating the fell motives of their oppressors."[29] Domingo's editorial, however, did not appease the secret police, who were alarmed by its ringing assertion that "in a world of wolves one should go armed, and one of the most powerful defensive weapons within the reach of Negroes is the practice of Race First in all parts of the world."[30]

Nor did Domingo's editorial appease Garvey. Accounts of what happened next differ. Some historians allege that Garvey expelled Domingo from the UNIA. Domingo, however, said that Garvey had been unhappy for some time with the tone of his editorials, and had "used the front page of the paper for a signed article setting forth his personal propaganda" to counteract Domingo's views. Domingo claimed that when Garvey charged him before the UNIA's executive committee with writing articles at variance with UNIA policy, the executive committee exonerated him, but that he resigned a few weeks later. Domingo further stated that his disparagement of the Black Star Line, which he characterized as "bordering on a huge swindle," was a major factor in his resignation.[31]

Harrison, a skillful writer, experienced editor, and famous exponent of the Negro First philosophy, was a logical choice as Domingo's successor as editor of the Negro World. Garvey probably also considered his knowledge of "every principle of Socialism" a decided advantage.[32] Harrison became an associate editor of the Negro World in January 1920. In its pages, and in a new collection of his articles published as When Africa Awakes in August 1920, Harrison continued his attack on Du Bois, his advocacy of a distinctive African sensibility, and his criticism of the Socialist party. All of these themes resonated with Garvey.

Treading on thin ice, Harrison accused Du Bois of harboring "the smoldering resentment of the mulatto who finds the beckoning white doors of the world barred on his approach. One senses the thought that, if they had remained open, the gifted spirit would have entered and made his home within them." He again raised the issue of intrarace colorism. In an inflammatory statement that was probably directed at Du Bois (but could equally have applied to Randolph and Owen, and indeed most American-born black leaders) Harrison charged that when whites selected Negro leaders they always chose "one who had in his veins the blood of the selectors.... The opportunities of self-improvement, in so far as they lay within the hands of the white race, were accorded exclusively to this class of people who were the left-handed progeny of the white masters." Blacks, imitating whites, also preferred the light-skinned of their group, and "hold the degrading view that a man who is but half a Negro is twice as worthy of their respect and support as one who is entirely black." Harrison warned that "So long as we ourselves acquiesce in the selection of leaders on the ground of their unlikeness to our racial type, just so long will we be met by the invincible argument that white blood is necessary to make a Negro worth while."[33]

Attacking Du Bois's antiquated educational ideals in Garveyite terms, Harrison declared that not "until the Negro's knowledge of nitrates and engineering, of chemistry, and agriculture, of history, science and business is on a level, at least, with that of the whites, will the Negro... measure arms successfully with them." Harrison disdained Latin and Greek in favor of this "modern knowledge--the kind that counts" with which blacks would "win for ourselves the priceless gifts of freedom and power... and hold them against the world."[34]

Harrison, complaining that black children received only an inferior version of the schooling that bolstered white arrogance and will to rule, demanded a racial education as well as a technical and scientific one. Because "the examples of valor and virtue on which their minds are fed are exclusively white examples," whites felt themselves superior and black students "think themselves worthwhile only to the extent to which they look and act and think" like their white oppressors. "They know nothing of the stored-up knowledge and experience of the past and present generations of Negroes in their ancestral lands, and conclude there is no such store of knowledge and experience. They readily accept the assumption that Negroes have never been anything but slaves and that they never had a glorious past as other fallen peoples like the Greeks and Persians have." Black colleges inculcated the traditional "little Latin and less Greek" instead of Hausa and Arabic, "the living languages of millions of our brethren in modern Africa." Race colleges should offer "courses in Negro history and the culture of West African peoples."[35] Harrison praised J.A. Rogers's The Negro in History and Civilization for proving that the Negro race "has founded great civilizations, has ruled over areas as large as all Europe, and was prolific in statesmen, scientists, poets, conquerors, religious and political leaders, arts and crafts, industry and commerce when the white race was wallowing in barbarism or sunk in savagery."[36]

Harrison also criticized Du Bois for his belief in moral suasion--a strategy that left ultimate power in the hands of whites. White people lynched Negroes, Harrison proclaimed, "because Negro lives are cheap.... But not all the slobber, the talk or the petitions are worth the time it takes to indulge in them, so far as the saving of a single Negro life is concerned." Harrison applauded John R. Shillady when he resigned from the NAACP in June 1920 because Shillady had lost confidence in the NAACP's methods of publicity and moral suasion. Shillady, a white, had been brutalized in Texas by a mob that included a local judge and constable. Harrison exclaimed that blacks needed "more of the mobilizing of the Negro's political power, pocketbook power and intellectual power (which are absolutely within the Negro's own control) to do for the Negro the things which the Negro needs to have done without depending upon or waiting for the cooperative action of white people."[37]

Harrison's Negro internationalism also sharply contrasted with Du Bois's version. Du Bois's Pan-Africanism stressed accommodation with the white colonial regimes, which represented their "possessions" at Pan-African Conferences. Harrison, by contrast, called for a unity of the darker races against European imperialism. White capitalists practiced internationalism for trade, credit, investment, and oppression; they opposed it for workers and colored peoples because "they wish to keep their subject masses from strengthening themselves in the same way."[38] The "capitalist international" would

unify and standardize the exploitation of black, brown, and yellow peoples in such a way that the danger to the exploiting groups of cutting each others' throats over the spoils may be reduced to a minimum. Hence the various agreements, mandates and spheres of influence. Hence the League of Nations, which is notoriously not a league of the white masses, but of their gold-braided governors.... To white statesmen "civilization" is identical with their own overlordship, with their right to dictate to the darker millions what their way of life and of allegiance shall be.

But the "darker millions" were fast developing a consciousness of kind and a unity of sentiment born of common suffering, and "the tendency toward an international of the darker races cannot be set back."[39]

Harrison asserted that blacks suffered the most from imperialism, although he acknowledged that whites at home and abroad (he specifically mentioned Ireland and Russia) were also victimized. Blacks, he said, must learn "from those others who suffer elsewhere from evils similar to ours. Whether it be Sinn Fein or Swadesha, their experiences should be serviceable for us." All colored races must unite and resist capitalist imperialism with weapons "as varied as those by which it is fighting to destroy our manhood, independence, and self-respect." The peoples of Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and the West Indies must recognize "that capitalism means conflict of races and nations, and that war and oppression of the weak spring from the same economic motive--which is at the very root of capitalist culture."[40]

The colored races, Harrison insisted, must unite with similarly-situated whites who would treat them as equals, rather than subsuming the world's majority under the rubric of white causes, whether Quakerism or communism.

The international of the darker races must avail itself of whatever help it can get from those groups within the white race which are seeking to destroy the capitalist international of race prejudice and exploitation which is known as bourgeois "democracy" at home and imperialism abroad. Until we can cooperate with them on our own terms we choose not to cooperate at all, but to pursue our own way of salvation.... We shall denounce every attempt [by whites] to stampede us into their camps on their terms until they shall have first succeeded in breaking down the opposing racial solidarity of white labor in the lands in which we live.... The temporary revolutionists of today should show their sincerity by first breaking down the exclusion walls of white workingmen before they ask us to demolish our own defensive structures of racial self-protection.[41]

Harrison asserted that blacks organized on racial grounds not for positive reasons of racial pride, but in response to white racism and oppression. "But those [whites] who meet us on our own ground will find that we recognize a common enemy in the present world order" and will "attack it in our joint behalf."[42]

Harrison, however, went beyond appreciating racial achievements as a defensive mechanism. While demanding a scientific and technical education for blacks, he also urged that African Americans "learn what [Africans] have to teach us (for they have much to teach us)"; only when Afro-Americans understood African customs, laws, and religions "will it be seemly for us to pretend to be anxious about their political welfare."[43] This highly unusual note contrasted Harrison not only with Du Bois, Randolph, and Owen, but also with Garvey. Harrison read and talked with intellectuals from "the darker races" abroad; he was impressed by what he learned, and predicted that after world blacks united, they would "see that it is to the[ir] interest and advantage to link up with the yellow and brown races."[44]

At a time when Du Bois was ingratiating himself with top governmental officials and priding himself on his American identity, Harrison bitterly attacked U.S. atrocities in the Caribbean. These outrages, he said, surpassed those in Turkish Armenia and Russian Poland. Haiti and Santo Domingo "have been murderously assaulted; their citizens have been shot down by armed ruffians, bombed by aeroplanes, hunted into concentration camps and there starved to death" with "the silent and shameful acquiescence of 12,000,000 million American Negroes too cowardly to lift a voice in effective protest or too ignorant of political affairs to know what is taking place." In Negro republics U.S. marines "murder and rape at their pleasure while the financial vultures of Wall Street scream with joy" over their plunder. Woodrow Wilson, whose government Du Bois yearned to serve, was for Harrison merely "the cracker in the Caribbean."[45]

Even while editing the Negro World, Harrison retained his analysis of imperialism as a capitalist phenomenon as well as a racial one. In When Africa Awakes he published an article rejected by "a well-known radical magazine" in 1918. "The White War and the Colored Races" combined a class and a race analysis of the Great War. Harrison succinctly explained that capitalism inevitably generated imperialism because wage slavery and the extraction of surplus value created the need for markets over which capitalists must fight. "Hence the exploitation of the white man in Europe and America becomes the reason for the exploitation of black and brown and yellow men in Africa and Asia.... And thus the selfish and ignorant white worker's destiny is determined by the hundreds of millions of those he calls 'niggers'." Although the interests of all workers were identical, Harrison emphasized that "economic motives have always their social side; and this exploitation of the lands and labor of colored folk expresses itself in the social theory of white dominion." Race and racism were therefore semi-autonomous variables, influencing events in their own right, even apart from or in contradiction to considerations of class. British workers, for example, believed that Africans were incapable of self-government; this racism encouraged a British imperialism that bolstered wage slavery in Britain as well as in its colonies.[46]

Reviewing Scott Nearing's American Empire in the Negro World in 1921, Harrison reiterated that "the most dangerous phase of developed capitalism is that of imperialism--when, having subjugated its workers and exploited its natural resources at home, it turns with grim determination toward 'undeveloped' races and areas to renew the process there." Militarism stemmed from the need for outlets for surplus capital as well as for markets, so newly colonized areas were forced to produce for the industrialized nations as well as purchasing their surplus products. Spheres of influence and protectorates resulted from the necessity of seizing foreign lands to preserve domestic profits. "Thus the lands of 'backward' peoples are brought within the central influence of the capitalist economic system." The international exploitation of peoples of color under the rubric of "the white man's burden" resulted from "the successful exploitation of white workers at home." All workers, therefore, objectively belonged to "an international of opposition" against capitalism. In an unintentional bow to Randolph, who had insisted that patriotism rather than racism accounted for the blindness of American workers to United States depredations abroad, Harrison concluded that "most Americans who are able to see the process more or less clearly in the case of other nations are unable to see the same process implicit and explicit in the career of their own country." Indeed, Harrison wryly commented that "each one of the imperialist groups can be perfectly trusted to tell the full and complete truth about the other. By collating these several national truths we can get the entire international story."[47]

Harrison recognized that the capitalist countries restructured not only the economies and governments of the colonized peoples, but also their cultures. Imperialist nations cultivated "new tastes" for consumer goods in the minds of their victims. They used enormous propaganda to convince Africans that happiness was unattainable without the products of consumer capitalism. Landless peoples--a class "which doesn't exist anywhere among black Africans except where white peoples have robbed them of their lands"--must "either work (for wages) or starve."[48]

While demanding a scientific and technical education for blacks, Harrison also urged that African Americans "learn what [Africans] have to teach us (for they have much to teach us)"; only when Afro-Americans understood African customs, laws, and religions "will it be seemly for us to pretend to be anxious about their political welfare."[49] This highly unusual note contrasted Harrison not only with Du Bois, Randolph, and Owen, but also with Garvey. Harrison read and talked with intellectuals from "the darker races" abroad; he was impressed by what he learned, and predicted that after world blacks united, they would "see that it is to the[ir] interest and advantage to link up with the yellow and brown races."[50]

Like McKay, Harrison foreshadowed the Negritude movement that became so influential in the 1920s and 1930s. Like Du Bois, Langston Hughes, and other African-American intellectuals (and indeed, like the Russian Slavophiles and Japanese and Chinese opponents of imposed "modernization"), Harrison believed that his people had an ethos distinct from that of the dominant and imperialistic whites, who were "so singularly constituted that they would rather tear themselves to pieces parading as the lords of creation than see any other people achieve an equal favor of fortune."[51] In a 1921 letter to Lothrop Stoddard (a white racist intellectual who shared Harrison's emphasis on race), Harrison defined Pan-Africanism as Africans' conscious desire "to rule their own ancestral lands free from the domination of foreigners however exalted and benevolent." It crucially included "a cultural movement" aimed at preserving "the soul of the African" by erecting a modern civilization upon the bedrock of Africa's own values and institutions. European technologies, however materially wonderful, were "at the same time spiritually disintegrating--not only to people to whom they are new but in their real essence." European experience demonstrated this. Africans did not consider material and technological progress as the ultimate good, as Europeans did. Curiously combining a conservative nostalgia with a class-conscious revolutionary consciousness, Harrison said that Africans "think that stability is more important to society than this restless, wearisome striving after the wind which always leaves 9/10th of your people short of such specific satisfactions as good clothing and shelter while mocking them with the mirage of civilization" and destroying "their Soul." Harrison concluded that "We older races prefer stability to progress; that is the wisdom of old stocks.[52]

Harrison urged that blacks "pattern ourselves after the Japanese who have gone to school in Europe but have never used Europe's education to make them the apes of Europe's culture. They have absorbed, adopted, transformed and utilized, and we Negroes must do the same." Mixing his analogies, Harrison urged: "Let us, like the Japanese, become a race of knowledge-getters, preserving our racial soul, but digesting into it all that we can glean or grasp, so that when Israel goes out of bondage he will be 'skilled in all the learning of the Egyptians' and competent to control his destiny." Whether blacks fight "with ballots, bullets or business, we cannot win from the white man unless we know at least as much as the white man knows. For, after all, knowledge is power."[53]

Consistent with the "race first" philosophy, Harrison and the Negro World endorsed the Liberty party, an all-Negro organization organized by Harrison, Edgar Grey, and William Bridges (editor of the Challenge), in 1920. The Liberty party ran James Eason, the UNIA's leader of American Negroes, for President. Although the Liberty party obviously could not elect its candidate, Harrison asserted that it would focus Negro votes "for the realization of racial demands." Such a policy would carry "race first" into "the arena of domestic politics," detach the Negroes from all mainstream parties (including the SP), and "enable their leaders to trade the votes of their followers, openly and above-board, for those things for which masses of men largely exchange their votes."[54]

Harrison asserted that "Just as one white man will cheerfully cut another white man's throat to get the dollars which a black man has, so will one white politician or party cut another one's throat politically to get the votes which black men may cast at the polls." Blacks would win acceptance only insofar as they used financial, political, and other force to "win, seize or maintain in the teeth of opposition that position which he finds necessary to his own security and salvation. And we Negroes may as well make up our minds now that we can't depend upon the good-will of white men in anything or at any point where our interests and theirs conflict."[55]

Although Harrison was by this time vehemently attacking African-American Socialists, he recognized that most blacks voted for the GOP, and concentrated his fire upon that party. He castigated the stupidity of the Negro Republican, who "would do anything with his ballot for Abraham Lincoln--who was dead--but not a thing for himself and his family, who were alive and kicking.... A Negro Republican generally runs the rhinoceros and the elephant a close third."[56] Harrison recounted the sordid history of the Republican party: its 1861 endorsement of a proposed thirteenth amendment that would have made "the slavery of the black man in America eternal and inescapable"; its policy during and after the Civil War of favoring Negro rights only "for the maintenance of its own grip on the government"; its shameless granting of "thousands of square miles of the people's property" to greedy Wall Street magnates and railroad speculators; and the corrupt bargain of 1877 by which "in order to pacify the white 'crackers' of the South, the Negro was given over into the hands of the triumphant Ku-Klux."[57] While the Republicans controlled the government "lynching, disfranchisement and segregation have grown." The Republican leadership acquiesced in this because a solidly Democratic South enabled the established Republican oligarchy to control Republican conventions with the help of "delegates who do not represent a voting constituency but [rather] a grafting collection of white postmasters and their Negro lackeys." Therefore, "the central clique of the party, controlled as it has always been by Wall Street financiers," can "foist upon a disgusted people" their candidates. Repeating the criticisms of other radicals, Harrison alleged that

The Republican party remains the most corrupt influence among Negro Americans. It buys up by jobs, appointments and gifts those Negroes who in politics should be the free and independent spokesmen of Negro Americans. But worse than this is its private work in which it secretly subsidizes men who pose before the public as independent radicals. These intellectual pimps draw private supplementary incomes from the Republican party to sell out the influence of any movement, church or newspaper with which they are connected.[58]

Harrison therefore supported "the new movement for a Negro party" and exclaimed that "if the Negro owes any debt to the Republican party it is a debt of execration and of punishment rather than one of gratitude."[59] Harrison urged "every Negro in the North who hasn't the vote to acquire it" and "all those who vote to use it." Negroes in the West Indies, Haiti, and the Virgin Islands could not vote, but the votes of Northern blacks could protect their off-shore compatriots from the "brutal war... and sexual and physical outrages perpetrated by the marines." Northern African Americans could also "secure the ballot for their voteless brethren in the South" and "compel enforcement of the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the American Constitution."[60]

Harrison demanded black leadership not only in politics, but in every area of black life. He extolled the masses and also praised leaders who both embodied the tendencies of their age and yet were nevertheless "souls that stood alone" above the howling mob in whose interests they labored. Harrison praised the Russian revolutionary intelligentsia for its selfless devotion to the masses, to whose yearning for liberty they imparted the power of knowledge. "Their only hope of reward lay in the future effectiveness of an instructed mass movement..... As knowledge spread, enthusiasm was backed by brains. The Russian revolution began to be sure of itself." Eventually the instructed masses overthrew not only the Czar, but the entire system of oppression. In the United States, Harrison averred, "those who have knowledge must come down from their Sinais and give it to the common people.... This is the task of the talented tenth."[61]

For the better part of a year Harrison believed that the UNIA embodied his dreams. In his Negro World editorial, "The UNIA," published during the pivotal August 1920 convention, Harrison said that the UNIA addressed the spiritual yearnings of the new Negro.

The essence of that appeal is the call to racial self-help and self-sufficiency. Begging, pleading, arguing and threatening are all methods addressed to the other man's mind. The Universal Negro Improvement Association eschews these ancient and futile methods of propaganda. The new Negro does not control the decisions of the other man's mind any more than did the old. But he does control his own body and brain, manhood and pocketbook; and out of these materials he can erect the splendid fabric of his future. To mass our manhood, our might and our money is the special object of this organization.

Here is a call to both the splendid idealism and the practical effort of the young Negro manhood. To have done with wishing and waiting; to replace a wishbone by a backbone, to finance our own future and to make for ourselves in the world of business, politics and culture that place which we deserve, without waiting for the good will of those who have been responsible for our being down--such are the ideals, aspirations and aims with which the Universal Negro Improvement Association makes its appeal to the young men of the race.[62]

Shortly after Harrison assumed editorship of the Negro World, a group of black Socialists launched the Emancipator, a weekly newspaper intended partly as a counterpart to Garvey's paper. Although historian Robert Hill argues that it "mainly criticized Garvey and the finances of the Black Star Line,"[63] the Emancipator propounded a coherent and sophisticated program that necessitated criticism of Garvey's opposing ideas. Indeed, its critique of Garvey and the UNIA, far from consisting of its raison d'être, stemmed ineluctably from its own positive vision. Domingo, recently ejected from the editorship of the UNIA's paper, took charge as editor and treasurer. Frank Crosswaith, a West Indian immigrant and the most prominent black Socialist of the later 1920s, was secretary, while Randolph, Owen, Anselmo Jackson, Cyril Briggs, and the up-and-coming black Socialist Richard Moore (the last two were also West Indian immigrants) were contributing editors.

The Emancipator exemplified, it said, a New Journalism that was itself "the inevitable consequence of the world-wide renaissance in social, political and economic thought," which increased knowledge through research. "The new journalism will introduce the Negro to the new world of history, economics, and sociology. It will turn him away from dead and valueless culture, the culture of eighteenth century classicism" and "supply a scientific chart and compass to guide the action of the New Negro in relation to national, international, industrial, social and political movements." The new journalism of the New Negro "proclaims to all the world its allegiance to the flaming and revolutionary cry, as formulated by the prophets Marx and Engels, 'Workers of the world unite. You have nothing to lose but your chains, you have the world to gain.'"[64]

The Emancipator boosted the Messenger, the Crusader (edited by Briggs), the People's Educational Forum, and the newly forming Friends of Negro Freedom. It advocated consumer cooperatives as a viable alternative to Garvey's racialized capitalism, urged that blacks join unions (especially the IWW) and strongly supported the SP. Its editorial statement united racial liberation with the abolition of class exploitation: "We shall uncompromisingly champion the cause of the oppressed of all lands; the right of workers everywhere to secure the full social value of the products of their toil; the prescriptive right of the native Africans to their ancestral domains." The Emancipator would free all races from "ignorance, race prejudice and wage slavery," and achieve for blacks an emancipation more complete "than that for which our fathers fought and died fifty years ago." Such a "New Emancipation" would be achieved by "INDUSTRIAL UNIONISM, COOPERATION AND SOCIAL DEMOCRACY."[65] The Emancipator would relentlessly criticize "the fallacies of uninformed leaders and the truckling subservience of corrupt contemporaries who sacrifice the race's interest upon the altar of Mammon."[66]

The Emancipator advocated consumer cooperatives instead of "wild-cat" and "bubble" financial schemes (by which they meant the Black Star Line and the Negro Factories Corporation). Cooperatives were organized for immediate benefits and "with the ultimate purpose of creating a society in which the people shall control and administer completely their own affairs... Beginning in this small way the workers gain experience for larger things." Cooperation was "free from politics" and abolished "both the gross profiteering of the moneyed aristocracy and the petty profiteering of the little tradesman"; it was "a genuine, permanent, successful means of self-help."[67]

The Emancipator argued that "the workers have united through their trade unions to better their conditions as producers--they must also unite as consumers to reduce the high cost of living." It urged that "if you form your own Cooperative Society you help yourself. If you wait for the State to help you depend on others.... If you do your part, the trade, the industry and the natural resources of the world will ultimately be in the hands of the people." No visionary scheme, cooperation "has been employed with such marvelous success by the downtrodden workers of other races" and was "the only effective means under the existing profiteering system whereby our people can benefit themselves, save money in their own pockets, and build industry for the Race."[68] Through cooperatives, "the people become their own store-keepers, wholesalers, manufacturers, bankers and insurance societies. Cooperation teaches the people how to provide, own and conduct their own housing, recreations and educational institutions, and ultimately to support all of their needs.... It excludes none" and substitutes "the spirit of cooperation and mutual aid for that of competition and antagonism."[69]

Editorials also urged that blacks "join a union, pay your dues, and fight like Hades to get square treatment on and off the job." The Emancipator admitted that unions often excluded blacks, or degraded them even after admitting them, and acknowledged that "these difficulties soon became a byword among Negroes, and the average member of the race felt no moral qualms at scabbing on white strikers." Yet some unions, especially those "mostly officered and composed of foreigners" (such as the ILGWU and the ACW), eagerly welcomed black members. Widespread segregation fostered misunderstandings by preventing contact between the races. Previously, the races mixed only "among denizens of the underworld," or during illicit interracial sex imposed by white men upon black women. Now, however, black and white workers mingled on the job, where they were "realizing their common interests." In New York, "black toilers" had joined the unions they formerly despised and had "fought scabs of their own race during strikes." The Emancipator noted that in New York "colored women are ahead of their men in appreciating the benefits of Unionism.... Women of different races are less race-conscious than men, and are able to subordinate racial bumptiousness in the interest of mutual advancement." While non-unionized black women worked for low wages under squalid conditions, "inside the union they are earning on the average more than their men folk."[70]

Echoing Messenger writers, Richard Moore eulogized as harbingers of a new day the white carpenters of Bogalusa for defending (at the cost of death or serious injury) a black union member. Crosswaith added that the capitalists

have used for their own selfish ends that child of capitalism--race prejudice. We find them using it not alone against the Negro worker and the white worker, but against white workers as such. They never hesitate to play the "Sheney against the Wop," "the square-headed against the Hunky," "the greaser against the Harp," and the Coon against them all.[71]

The capitalists were internationalists, Crosswaith said, as their League of Nations demonstrated; the workers must similarly unite across racial and national boundaries. The Emancipator cited rich Negro exploitation of poor black workers in the British West Indies as proving that "oppression in these islands is more economic than racial, although it must be admitted that racial dissimilarity aggravates the question."[72]

The Emancipator reserved its highest praise for the IWW, which it characterized as a militant, uncompromising, and racially egalitarian strike force.

With the exception of Negroes there is no group in the United States that has been subjected to more abuse, misrepresentation and persecution than the Industrial Workers of the World.... To read the history of the IWW is like reading the history of the Negro. Mobbed and tarred and feathered by the "best citizens," driven from their homes by armed thugs, lynched by silk-hatted savages, imprisoned by misnamed justice, and libeled by the Press, the members of the Industrial Workers of the World have run the entire gamut of peculiarly American modes of persecution.

Withal they have stuck to principle, admitted Negroes to membership and defied the American psychology of discriminating against black toilers. The success of the Marine Transport Workers Union in Philadelphia eloquently testifies to this fact.[73]

Negroes, the Emancipator said, should defy racist persecutors and investigate the principles and practices of the IWW, rather than joining its lynch-mob opponents. The Emancipator also praised an IWW local in Vancouver, British Columbia, for uniting workers of three continents and seven races in one organization. "One representative for each craft, and one for each race, are working together to formulate a joint wage scale for mill workers"[74] that the IWW would enforce.

The Emancipator quoted white IWW leader Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, who, speaking at a People's Education Forum, "pointed out what seemed an ineradicable human tendency to oppose new ideas and to condemn their proponents as enemies of society." These ideas "though condemned in their day, become the dominant ideas of the next day." The black workers of Elaine, Arkansas, and SP leader Eugene Debs were exemplars of this. "Socialists and Industrial Workers of the World, idealists who sacrificed self and gave all they had for a cause, were today behind bars in various Federal prisons. Conscientious objectors were being tortured and subjected to the vilest treatment imaginable, because these men were true to their consciences and believed that man should not slay his brother man.... These men were true apostles of progress; they sought to improve themselves through organization, and by so doing leave the world a happier and safer place to live in. But like all pioneers of progress they are called upon to pay the price." Criticizing a xenophobic Negro editor, Flynn said that "Nothing is more disgusting than for an oppressed people to be bigoted and intolerant; they should be the greatest opponents of oppression themselves."[75]

Crosswaith similarly warned that "the pages of history tell us that whenever great changes occur, when great principles are involved, as a rule, the majority are wrong. In every age there have been a few heroic souls who have been in advance of their time, who have been misunderstood, maligned, persecuted, sometimes put to death; then long after their martyrdom monuments were erected to them, and garlands woven for their graves. We see today the mad rush of those who would stop the mighty hand of evolution (if they could) jailing, hounding, and deporting men for having ideas in advance of their time...." When the honor roll of history was compiled, he asked, would the names of Negroes be absent? "Fellow workers of my race.... Your duty to yourself, to your unborn and to society demands a decision. I have decided for myself and have cast my lot with those who 'live by working,' to survive or perish." Owen, speaking at the People's Educational Forum on "Destruction: the Forerunner of Progress," said that blacks must destroy "prejudice, discrimination, jim-crowism and lynching," the illusion that the United States was a free country, and "the belief of Negroes that this is their country when they own so little of it." Because "like causes would produce like effects," American repression of dissent might make it "necessary for the American people to copy the methods used by the Russians to rid themselves from tyranny."[76] The Emancipator endorsed the Crusader's (and the UNIA's) demand that blacks not fight for the United States against their racial brethren in Haiti or Mexico--or, it added, its class allies in the Soviet Union.[77]

The Emancipator also denounced the New York legislature's expulsion of its five SP members, and excoriated with special fervor the black assemblymen (including Clifford Hawkins) who voted for this expulsion. The Emancipator exclaimed that support of such Czarist methods both followed from and provided further precedent for the similar disfranchisement of people on account of their color. "If men can be disfranchised because their color does not meet the approval of a dominant group, it then becomes but an easy step to deny a voice in government to another group whose opinions do not come up to the standards set by their dominant rivals.... The attempt to outlaw opinion is but part of a plan to reduce New York to the mental level of Czarist Russia, Mississippi, Georgia and Alabama."[78]

The Emancipator found similar evidence of persecution and oppression close to home. Its second issue featured a screaming headline on the first page, "GOV'T SCORES NEGRO RADICALS. Suppressed Report Condemns Fearless Negro Agitators." This article--the first in a series--excerpted secret police denunciations of Garvey, Randolph, Owen, and Domingo for advocating social equality, alliance with white radicals, opposition to the Wilson administration and its policies, and self-defense against white terrorism. The Department of Justice document also attacked an increasing "race consciousness... antagonistic to the white race and openly, defiantly assertive of its own equality and even superiority." The secret police worried that the radical papers were edited by "men of education" and were "not to be dismissed lightly as the vaporings of untrained minds." The report concluded that "the Negro is 'seeing red.'" The excerpts in the first and second Emancipator installments concentrated on Garvey, whom the Emancipator thus implicitly identified as a racial and radical compatriot.[79]

The Emancipator's Socialist and internationalist philosophy, however, necessitated criticism of Garvey. The Emancipator did sometimes praise the UNIA leader, at other times favorably quoted him, and always denounced U.S. surveillance of his organization. Yet its first issues sniped at Garvey and his numerous enterprises, often without naming them. For example, in an oblique slap at the Negro World (which published news from the West Indies in a separate section on page two) the editors vowed that, opposing "any form of segregation in theory and in practice.... We shall not insult West Indians by rigidly excluding matters pertaining to them from our front page, nor shall we publish such news on a segregated page. Instead, we shall treat all news alike--upon [its] intrinsic merit." The editors would "avoid boosting any individual personality" and instead "print items that are of general interest."[80]

Domingo's paper also warned blacks against "autocrats who, manipulating the psychology of Negroes, are engaged in the futile but self-enriching task of Empire building." The Emancipator criticized unnamed "wild-cat business propositions," which, it admitted, were spawned by high wartime wages, the new racial consciousness, and resentment against "the galling economic dominion" exercised by "arrogant business men in purely Negro neighborhoods." Many such schemes, however, were "overambitious and oblivious to ordinary economic realities" and "kept alive by deceptive propaganda and questionable financial methods." Their inevitable failure would "injure the race. It will discourage future enterprises and impoverish many" who invested. Citing the sad history of overambitious Afro-American businesses (the Freedman's Bank, the True Reformers Bank, the Afro-American Realty Company, and Chief Sam's enterprises), the Emancipator criticized "ignorant mountebanks" and warned that "business is not as easy of performance as getting up upon a platform and making wild, ignorant, exaggerated statements.... We are a poor people, comparatively; we are despised as being inferior and we cannot afford to weaken ourselves financially by promoting 'bubbles' which when they burst supply our enemies with a powerful argument as to our alleged inferiority."[81]

On March 27, 1920, the Emancipator began "An Analysis of the Black Star Line," a series by Messenger writer Anselmo Jackson. While at first seemingly dispassionate, objective, and analytical, Jackson increasingly cast severe doubt upon the BSL's viability and Garvey's honesty. (At one point he averred that Garvey's racial philosophy and temperament stemmed from "the fact that his head has the shape of the German type.")[82] A large headline screamed "Black Star Line Exposed"; Jackson echoed the claim of Brigg's Crusader that the BSL's flagship the Yarmouth was in reality owned by a white company. (This accusation, based on a highly dubious legal technicality, doubtless weakened the credibility of the Crusader's later, accurate charge that the BSL lied about its putative ownership of another vessel, the Phyllis Wheatley.) The next issue publicized the Crusader's $500 reward for anyone proving that the BSL actually owned the Yarmouth. The Emancipator also revealed that Garvey patronized white businesses and professionals in preference to race enterprises, even those owned by UNIA members. This illustrated "the point that business is business and knows no color line.... The good old Socialist doctrine of the power of a man's material interest causes some interesting racial complications."[83]

The Emancipator also criticized Garvey's Back to Africa plans, warning that Africa lacked the common language, religion, and culture necessary for nationhood, and reminding its readers that Liberia was surrounded by rapacious colonial powers that would crush any anti-imperialist agitation. Echoing Messenger editorials, the Emancipator said that "modern empires are not created by fiat. They have an economic foundation which is buttressed by the military, the navy and the police. For these three powerful arms to be created, and for the first to be firmly and securely built, those who hope to profit from imperialism must control the State." Even Germany had been ignobly crushed; was this "an example for imperially minded Negroes who control neither State, army, navy, nor police?" The Emancipator concluded that "the way of empire should not be the way of the Negro race.... Empires are their own grave diggers!"[84]

Crosswaith similarly marvelled that in an age when monarchies, empires, and other oppressive institutions were crumbling into dust, "the race which has suffered most from these institutions" would believe that "the creation and possession of the most cursed of these institutions (Empires) for themselves will aid them in their just fight for a place as equals in the ranks of civilized society." Although some false leaders promised that blacks could oppress their exploiters, "with Africa as our Empire, there will still be ragged, underfed, and poverty-stricken Negroes. All that we will have done will be to have exchanged our white parasites and profiteers for black parasites and black profiteers. Such a change will not help the race to any extent; it will certainly benefit the Emperor and his henchmen!"[85]

Domingo provided the most brilliant and nuanced critique of Garvey's plans in his article, "Africa's Redemption." He readily conceded that "it is the natural instinct of any people who are bound together by ties of race to desire to control their destiny. Every right, natural or otherwise, justifies this feeling.... Deep down in the soul of every race there is the yearning after equality with other races, the longing to see one's own type achieve the highest, the best, the noblest." Education kindled "a constant struggle for the liberation of their racial souls. First comes liberation of the racial mind, next liberation of the group. Understanding this, empires have always striven to kill the racial and national individuality of a conquered people." The British, for example, waged relentless war against the native cultures of Ireland and India.[86]

Comparing India and Africa, Domingo next ensnared himself in a contradiction. "The Indian population is large and it is difficult to destroy the history of a people who have a written language," he said. "Study of their history, as well as economic and political oppression, has stiffened the national backbone of India and created unity where there was disunity, nationality where there were nationalities. In India race and nationality are becoming identical. When an Indian dies for India, he dies for his race, his nation." Domingo denied that Africa, which lacked a written language or common culture, could unify itself as India had. Yet as he admitted, India had lacked a common culture, language, and religion; and Africa was united by a common history of European exploitation and by its communal culture. "The natives, as Blyden and Dudley Kidd point out, are natural Socialists. They think in terms of the 'we' rather than the 'I.' On the coast European artillery has broken up the communal system, but it remains intact in the interior." On Domingo's own reckoning, therefore, Africa could unite against European oppression much as India had.[87]

Domingo insisted that the redemption of Africa did not mean "the introduction of European political methods and social systems that are incomprehensible to the native, but recognition of the truism that to break up the African communal system is to injure, not aid, the natives." Prosperity and self-government "cannot be forced upon the Africans from the outside" but "must develop in Africa" and "be African in character. But Africans abroad can help. They can help to destroy the system that dooms the majority of 'civilized' Africans to poverty and denies a race the divine right to order their life as they deem best." Achievement of this requires the destruction of that "hideous monster," imperialism.

Does redemption of Africa mean the foisting of Christianity upon the people? Or breaking up their communal system and introducing private ownership in land? Does it mean that the descendants of Africans from the West Indies and the United States who have lost their true racial identity must introduce their acquired culture into a land with a culture that reaches back into the dim past? Shall Africans of the dispersion try to supplant the communal organization of tribes like the Fanti in which the dominant aim is the 'man' as opposed to the 'I' of the West Indies? Is primitive socialism to give way to capitalist [brutality and] individualism?

To redeem Africa one must work with the materials in Africa; one must be practical. The best of European civilization in industry, art, literature and science--particularly science--must be given to Africa, not to Europeanize the African, but to develop his racial culture to the zenith of its possibilities.[88]

Liberation of Africa required an understanding that Africa's oppression was "mainly economic and a fruit of the capitalist system."

Africans residing in imperialist countries battening off of the colonized world "can best redeem Africa by helping to break up the system." The real enemies of the colonized peoples were not "the ignorant white soldier or the more ignorant black soldier," both of whom believed in white superiority; rather, it was "the small group of men who get concessions for exploiting" Africa and Haiti and despoiling "their great agricultural and mineral wealth." Therefore, "to redeem Africa, Africans in Africa and Africans abroad must try to communalize science, art and industry; they must recognize the true African soul which has its roots in the economic system of the natives and try to develop that soul." Africans abroad must overthrow the system "responsible for the present political degradation of Africa and their own oppression in the West Indies, Central and South America and the United States. To do this calls for clear thinking and recognition of the fact that Africans are not the only ones who are the victims of capitalistic exploitation."[89] Africans abroad, Domingo concluded, must form consumer cooperatives, join industrial unions, and ally themselves with white radicals working for the destruction of capitalism and imperialism. In addition they must inculcate in themselves "a true conception and pride in their racial type which will expand their souls and give them the necessary weapons for achieving a glorious future."[90]

Garvey and his organization were not the only targets of the Emancipator: the weekly also castigated Du Bois for his utopian illusion that altruistic, reformist whites would materially aid the cause of black liberation. "The line of division is not one of race or nationality but one of CLASS," it said. Between the two contending classes stands a group "who, while logically of one class, affect to have conquered their material interests and seek to attain a position of angelic impartiality which is founded upon a just valuation of pure morals." Such "liberals" preach class conciliation and a capital-labor alliance (with labor the junior partner), and help the unabashed capitalists "exploit the land and labor of darker peoples" for their "mutual benefit." The Emancipator charged that "most of [the NAACP's] officers are white capitalists or beneficiaries of capitalism, and the colored officers are themselves potential capitalists. Labor and Capital are preparing for the last grapple and Capital, being shrewd, looks with longing eyes at 15,000,000 people as allies (or tools)."[91]

Whites, the Emancipator exclaimed, could not be talked out of exploiting the darker races or into decent behavior. In an editorial implicitly criticizing both Garvey and Du Bois, it said that "being good patriots, good Christians or splendid conservatives" would not bring Negroes "surcease from oppression." The Emancipator continued:

Men oppress their fellows for something more substantial than their failure to be good patriots, Christians or conservatives; they oppress because it PAYS. It may not pay the poor ignorant and "patriotic" soldier who actually does the oppressing but it certainly pays the cunning politicians, financiers and concessionaires who direct the oppression.

Oppression of a group, a race, a nation, is reduced in the final analysis to exploitation of their land or labor.

In America all Negroes are not lynched and jimcrowed, but over 99 per cent of them have their labor exploited. They are in truth the race, and their exploitation... [is not] lessened by their opposition to foreigners, Socialism and radical thought. Recognition of this fact should compel an intelligent and friendly attitude towards movements which seek to remove the evils of poverty and squalor.

A slave should not be loyal to his master, nor should he seek to exchange masters by creating some from among the members of his own class....[92]

Although the Emancipator propounded a wide-ranging analysis and program of reform, its critique of Garvey and of the BSL enraged Harrison, then editing the UNIA's Negro World. At the conclusion of the 1917 elections Harrison had remained pro-Socialist, although no longer a member of the party. However, fractures in Harrison's relationship with his old comrades had proliferated. Mary White Ovington's "bossy and dictatorial note," which had almost commanded that Harrison cease publishing the Voice, infuriated him. The AFL's major role in the East St. Louis pogrom indirectly redounded upon the SP, and Harrison's call for Afro-Americans to "scab [the AFL unions] out of existence" contravened Socialist practice. (Even that bitter AFL foe, the IWW, expelled members who scabbed on AFL strikes.) In The Negro and the Nation (August 1917) a compilation of some of his articles, Harrison commented that he had left the SP "partly because, holding as he does by the American doctrine of 'Race First,'" he preferred working "among his people along lines of his own choosing."[93] Chandler Owen's subterfuge over his debate with Harrison in December 1917 only deepened Harrison's alienation.